<B>Overtaking:</B> Turning the corner.

By Peter McLaren

All memorable motor races contain overtaking but, despite changes to car design, tyres and the qualifying format, Formula One is yet to see the kind of regular passing that drivers and fans want to see.

For a variety of reasons, not least the broadly equal-excellence of current designers and drivers, overtaking in F1 will never be easy - but is there more that could be done to the racetracks themselves to give drivers that are clearly quicker than the car ahead a realistic chance to pass?

By Peter McLaren

All memorable motor races contain overtaking but, despite changes to car design, tyres and the qualifying format, Formula One is yet to see the kind of regular passing that drivers and fans want to see.

For a variety of reasons, not least the broadly equal-excellence of current designers and drivers, overtaking in F1 will never be easy - but is there more that could be done to the racetracks themselves to give drivers that are clearly quicker than the car ahead a realistic chance to pass?

Even 2006 spec cars are able to follow a slower opponent reasonably closely. The problem is that it often remains a giant step to make the transition from following to overtaking. But overtaking does still occasionally occur, almost exclusively in hard braking areas/corner entry, so could the design of these 'zones' be specifically modified to maximise overtaking opportunities further?

Track width:

At this point, it's worth looking at two-wheeled motorsport and why so much overtaking takes place. Ignore the fundamental differences between the machinery and look closely at what happens when two (or more) machines approach an overtaking zone.

One of the reasons why passing is more plentiful is the ratio of motorcycle width to track width: When a motorcycle enters a corner there are far more options available - even if a 'defensive' rider moves across and covers the inside there are usually still several alternative passing lines available on both the inside and outside.

As such, the odds of overtaking are much more favourable - a defensive rider simply cannot cover every line - but because F1 cars are wider (and braking areas short) a defensive driver can often cover both the inside and outside lines by simply sitting near the middle of the track.

Therefore, if the width of the track in the overtaking zones is significantly increased then the chances of overtaking also correspondingly improve - as proven by the Hockenheim hairpin last weekend. More potential racing lines also means a more technical corner, which rewards the most talented drivers.

Apex position:

As well as track width, the position of the corner apex is also important because whoever reaches the apex first almost always wins the corner. In general, an early apex favours the defender, while a late apex helps the attacker, so the apex needs to be moved as far as possible around the corner for overtaking purposes.

Combine these two principles and you get something similar to the revised 90-degree and hairpin corner designs shown in the middle picture (click to enlarge).

Why these designs might help:

In theory, such designs could help overtaking in the following ways:

1) Aiding the block pass.

This is the most common type of pass, which occurs when a following driver dives inside the racing line under braking in order to reach the apex first. A successful pass is made, not because the following driver is faster around the corner, but because, having reached the apex first, their presence on the racing line then 'blocks' the car behind and stops it using the extra corner speed possible from following the ideal racing line.

By increasing track width, keeping the ideal racing line across to the outside as much as possible and delaying the apex, the attacker has a much better chance of reaching the apex first.

2) 'Forcing' the driver ahead off line.

By increasing track width and delaying the apex in such overtaking areas, the defending driver is likely to be 'forced' to move off the ideal line to cover the inside and prevent such a block pass from taking place.

The attacking driver then has two options; either to go further inside (if there is room) or to switch to the ideal outside (racing) line vacated by the driver ahead.

By increasing the track width the opportunity to go further inside is, unlike at present, still likely to exist but, because the speed difference between the inside and outside lines is now much more exaggerated, the following driver can also gain much more speed by switching to the outside line, giving a much better chance of drafting pass the car ahead on corner exit or into the following turn.

Camber and grip changes:

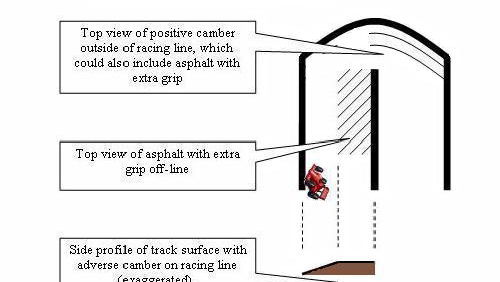

Additional possibilities to prevent the dreaded one-line procession would be for circuits to deliberately lay an extra grippy form of asphalt off the racing line, on the approach to medium and hard braking corners, to reduce the current disadvantage suffered by moving away from the racing line to try and overtake.

In other words, this grippy asphalt would compensate for the increased traction provided by the clean racing line and the reduction in grip caused by the 'marbles' of rubber debris and dirt left off line.

Part of this process could simply include thoroughly cleaning the racetrack on a Sunday morning to remove both the rubber on the racing line and the debris off it, to leave a more consistent amount of grip across the track. This might prove unpopular with teams due to the possible changes to car handling, but it would be the same for everyone and might make for more unpredictable racing.

Another way of influencing grip levels for the purposes of overtaking would be to camber parts of the braking areas.

As an example, the asphalt could be kept perfectly flat from the inside to the middle of the track, but then fall away to the outside. The outside line would therefore be off-camber, while the inside would be flat (as illustrated on a 'standard' hairpin corner in the lower picture, click to enlarge). Such camber changes can occur naturally on street circuits, but are, at present, not specifically tailored for overtaking purposes.

The outsider of the corner itself could also be banked from middle to exit to again aid the creation of multiple lines (corner entry would remain flat to avoid 'launching' an out-of-control car into the air).

Finally, the importance of the corner that leads onto a long straight has long been known for overtaking, with low-speed corners preferred to avoid disturbing the aerodynamics of the chasing car.

However, perhaps a more effective design would be to keep the low speed characteristic - but make the corner a blind, narrow, multi-apex, multi-camber challenge... in other words, an ultra-technical turn that would highlight - and more importantly punish - any small error all along the straight and into the following corner.