Who is leading the last F1 tech trends of 2018?

The development race for this season is all but over.

While there is still some performance to be found through car setup and further understanding of the packages the teams already have, only a few new items have trickled onto the grid over the past few races.

Ferrari, admittedly, went down a bit of a blind alley since the summer break, and have since reverted to some older specification suspension and aero components that have brought them back into contention – too little, too late, perhaps.

The development race for this season is all but over.

While there is still some performance to be found through car setup and further understanding of the packages the teams already have, only a few new items have trickled onto the grid over the past few races.

Ferrari, admittedly, went down a bit of a blind alley since the summer break, and have since reverted to some older specification suspension and aero components that have brought them back into contention – too little, too late, perhaps.

However, even in the dying stages of the season, Formula 1 never fails to disappoint in its relentless pursuit for engineering perfection: The legality of the Mercedes has been called into question in recent weeks, and the emergence of Ferrari’s latest ideas surrounding the floor area has taken no less than one week for another team to copy. Cat and mouse to the end, it would seem.

It would be fair to say that Formula 1 and tech controversy are synonymous with each other. Following the intriguing new developments at the rear of the Mercedes back in Singapore, rivals – namely Ferrari – have contested the legality of their wheel rim design, or rather the wheel spacer.

To understand the argument we must first evaluate the importance of the wheel’s design, especially in relation to tyre temperatures.

To reduce unsprung mass the wheels are often made from aluminium or magnesium alloys. These materials are strong enough to withstand substantial forces, but also have relatively high heat conductivity.

This means that heat generated by the brakes inside the hub assembly is transferred relatively easily into the wheel, which is then conveyed into the tyre carcass. This is done by both convection – hot air circulating between the hub and the wheel – and conduction, where the wheel locates to the hub.

To control heat transfer from the wheel to the tyre, teams work extensively on the rim’s surface area and aerodynamic characteristics to better circulate the rotating air. Knurled surfaces and carefully designed hole patterns are just two examples of how this problem can be addressed.

The technical regulations permit the use of spacer between the hub and the wheel, which are traditionally used to increase the stability of the car.

On the Mercedes the wheel’s eight locating pegs are installed on such a spacer, which align with corresponding holes on the wheel hub; there are 24 holes on the hub, leaving 16 holes unoccupied when the wheel is fitted to the car.

Ferrari have queried how this spacer is involved with the rest of the wheel assembly, in particular if it is part of an aerodynamic system; the question of legality is whether it is a movable aerodynamic device. In the past we have seen deliberate channelling of air through the brake ducts and hub, out into the open air via the axles to generate outwash around the tyre.

The spacer appears to be made from an entirely different material to the rest of the rim, indicating a different, probably lower thermal conductivity. My guess is that the spacer, perhaps machined from some sort of steel, is used simply to soak up heat from within the hub and retain it at the axle, as opposed to letting the centre of the rim absorb it. This reduces the ease in which heat can conduct through the spokes into the rest of the rim.

In recent races, Mercedes have drilled small holes into the spacer that directly correspond with where the unoccupied holes would be when the wheel and hub meet, suggesting that the engineers want to further increase the heat sink into the spacer.

Heat from the brake disc – which can exceed 1000 degrees Celsius – vents through the unoccupied holes and pegs, transferring into the spacer via convection and conduction respectively; the drilled holes simply help bring that heat further away from disc and perhaps closer to an area where air circulating in the wheel can absorb it.

The FIA have deemed that what Mercedes is doing is legal because the drillings appear to offer only a benefit in heat transfer; the fact that the spacer rotates in the same manner as the rest of the wheel assembly also suggests that any aerodynamic effect would also be difficult to control through such small orifices.

Furthermore, the FIA’s verdict indicates that there is no internal duct-work going through the hub assembly to push air out of the wheel face.

Although their legality has been cleared up, there are still some intriguing questions left unanswered about the wheel design.

Perhaps to avoid attention while the matter was cleared up, Mercedes used a conventional blank spacer last week in Austin and covered an entirely different set of holes on the inside face of the wheel facing in on the axle with silicone. The theory I have presented here doesn’t explain why the team chose to do this, suggesting that there might be a connection between the two sets of holes.

We really need a glimpse behind the spacer of the rim itself to completely resolve the mystery…

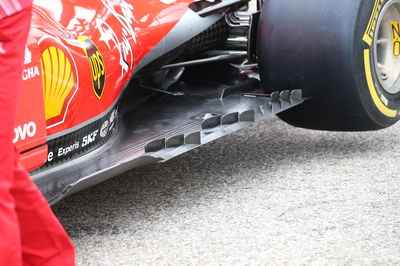

On the aerodynamic front further developments have been spotted on the floor of the Ferrari in recent races, with rows of vortex generators have been placed on top of the longitudinal floor slots that run along the flanks of the car.

Red Bull decided to immediately replicate the idea within a matter of days, trialling their own version on Friday.

The position of bodywork provides us with a clearer understanding of how the airflow moves in along this region: the outwardly turned vanes suggests that there is a clean band of flow that would normally be left unexploited and end up coming into contact with the rear tyre.

With the new bodywork in place the flow is instead diverted sharply and allowed to form a vortex rotating towards the car’s centreline, shielding the sides of the floor from the front tyre’s wake. This is not a new concept in this area of the car, but it is certainly enhancing the effects that already exist.

These latest developments have also made us pause to reassess exactly what the function of the floor slots is.

Rather than forming a vortical structure, perhaps the air flowing through the slots is drawn with such energy from the low pressure beneath that it is simply diverted cleanly to an area of choice, the most obvious being the gap between the rear tyre and diffuser wall. Again, not a new idea by any stretch but a significant refinement – almost all teams have implemented these intricate cutouts into the floor, which have no doubt contributed to the impressive performance of this year’s cars.