'Wings, Chins' remain under stricter 2020 MotoGP aero rules

The swingarm spoilers, nicknamed 'spoons' or 'chins', that ignited a feud between manufacturers in Qatar this year will still be legal under MotoGP's stricter aerodynamic regulations in 2020.

However, the devices - plus any other areas of the bike with 'aerodynamic effect' - will now fall under Aero Body rules, which allow only one design update per season.

All current fairings and 'integrated wing' attachments will also remain legal, but with much clearer limits on size and shape to act as a "roof" for future development.

The swingarm spoilers, nicknamed 'spoons' or 'chins', that ignited a feud between manufacturers in Qatar this year will still be legal under MotoGP's stricter aerodynamic regulations in 2020.

However, the devices - plus any other areas of the bike with 'aerodynamic effect' - will now fall under Aero Body rules, which allow only one design update per season.

All current fairings and 'integrated wing' attachments will also remain legal, but with much clearer limits on size and shape to act as a "roof" for future development.

"We believe that once you have a good base with the technical regulations, stability pays off in terms of cost control and closing the technical gap between the teams," MotoGP Director of Technology Corrado Cecchinelli told Crash.net.

But in the case of aerodynamics, there had been no choice but to act: "We did something only because we had a problem to address."

MotoGP banned the use of normal 'protruding' wings on safety grounds at the start of 2018 but gave the green light to 'integrated' wing devices.

The deliberately minimal regulations rely on Technical Director Danny Aldridge having the final say on what is allowed, often meaning a back-and-forth design process between Aldridge and a manufacturer until an agreement is reached.

Helped by an ever-growing list of guidelines from Aldridge, plus use of a metal jig to check the main measurements, most manufacturers have now settled on similar variations of hollow loops or box-style wing attachments on the side and/or front of their fairings.

But unexpected developments at the other end of the bike caused more controversy, with four manufacturers (Honda, Suzuki, KTM and Aprilia) protesting Ducati's use of a swingarm-mounted 'tyre cooler' ('spoiler/spoon/chin') at the Qatar season-opener. Yamaha, which inspired Ducati's design by creating an earlier 'rain deflector' in the same area, did not protest.

The swingarm device argument escalated to the MotoGP Court of Appeal, which confirmed its legality, but the case underlined why more detailed aerodynamic regulations were needed for 2020.

"Basically, we had a problem of borderline interpretation of the regulations and so we had to act to narrow this border," Cecchinelli said.

"I hope I can speak for the manufacturers when I say that they are all very happy with the measures we took, because it will be clearer for everybody."

So what will change in 2020?

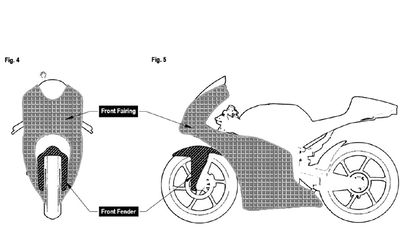

The current Aero Body rules only apply to the Fairing and Front Fender.

Swingarm Spoilers

"The infamous 'chin'… will still be legal, but now it will become a homologated part," Cecchinelli explained.

"As you know, we split the outside of the motorcycle into different areas that we call the Aero Body. You are only allowed to make one design update to each Aero Body area during the season.

"At the moment there are two Aero Body areas: The Fairing and Front Fender. From next year there will be another Aero Body area covering the swingarm."

That means: "If you change the design of the 'chin', including if you simply remove it completely, it will count as your one update for the season in that area."

To pre-empt a repeat of the swingarm saga, the same Aero Body restrictions will also apply to any other part of the bike that is deemed to have "an aerodynamic effect".

"For instance, the fork leg cover will be automatically considered as part of the Aero Body. So it is allowed to be shaped [aerodynamically], but that shape can only be changed once during the season," said Cecchinelli.

'Aerodynamic effect'

Ducati's rivals protested the 'chin' on the grounds that it was 'primarily an aerodynamic device'. The Italian factory countered by presenting evidence that the device's main purpose was to make the rear tyre cooler, with downforce described as a minor 'secondary' effect.

Much depends on how you interpret the words 'aerodynamic effect', an agreed definition of which will now be included in the 2020 rules.

"There will be a very complicated and, in some ways, still subjective wording to define 'aerodynamic effect'. But it will be much clearer than now," Cecchinelli said.

"It basically says that, every component or part of a component that has a design that is not necessary for its basic function will automatically be considered part of the Aero Body.

"That means if you have a normal swingarm shape it won't be considered part of the Aero Body, because the shape is purely to carry out a mechanical function.

"But if you were to sculpt the swingarm surface using a monocoque design to include the 'chin' as one piece, then the whole swingarm would become part of the Aero Body. So be careful, because then you could only change the swingarm design once during the season."

To avoid that scenario, Cecchinelli expects all manufacturers to run a non-aerodynamic swingarm shape, with the aerodynamic 'chin' part bolted on separately.

Dimensions, angles, radius

In terms of the main fairing design and associated wing attachments, Cecchinelli said that for 2020 "more dimensional constraints" would be added, including "radii, angles and measurements" to put a "roof for the future."

"There will be a much smaller grey area, but there will always be some grey area," he warned.

All of the fairings currently seen on track would still be legal next season, to avoid unfairly penalising anyone.

"Nobody has to change their current designs. In every respect we checked the existing fairing designs and set the new, more precise limits using what exists now, so nobody has to take a step backwards."

'More patches in future'

Cecchinelli describes the steps taken for the 2020 rules as "a good job, meaning not bad and not perfect" but knows new aerodynamic issues will eventually arise.

"Honestly, it wasn't that difficult to reach a better solution because the manufacturers were all very collaborative. But don’t expect that there won’t be any more pit holes in the future and don't call us stupid if it happens! Because this is the way it goes," he said.

"The [manufacturers] have far more people than us and their job is to go to the extremes.

"Remember, Formula One has decades more experience than us with aerodynamic rules and they still have problems. Someone is smarter and then the organiser has to catch-up. It's part of the game.

"It's always a case of putting patches over the holes, just like adding a software update for your mobile phone to meet a changing situation. So the rules will need to change again one day, but I hope not very soon."

Indeed, Cecchinelli confirmed that no significant new technical rules are in the pipeline for the next five-year contract between the manufacturers and Dorna, which starts in 2022.

"There's an agreement to aim for technical rule stability over the term of the current contract, which expires in 2021," he said. "But it is also our intention not to change anything significant at the beginning of the next term, starting from 2022.

"We are not just waiting for the current contract term to expire before introducing something big for 2022. The plan is always consistency."

That includes no big changes to the single electronics.

"We have no plans, in any of the categories, to make any important software evolutions. We are always changing small bits, but not something big like removing [corner-by-corner set-up] or traction control," Cecchinelli confirmed.

"That also means the Moto2 ECU will be the same next year, so no traction control."