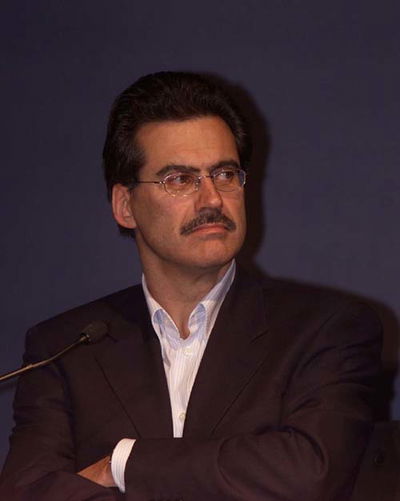

Q&A: Dr. Mario Theissen.

Q:

During budget discussions, it was proposed to limit the number of engines used on GP weekends to two per car. What is your take on that?

Q:

During budget discussions, it was proposed to limit the number of engines used on GP weekends to two per car. What is your take on that?

Dr. Mario Theissen:

The current norm is one engine per day. If you had to use the same engine for qualifying and for the race, it would naturally improve running performance and would have to be taken into account in the design. Essentially we view this proposal in a positive light. It would reduce the number of engines needed. But above all, it would dispense with the design and development of special qualifying engines, which would increase costs even further without any apparent benefit to the sport.

Q:

Which synergies between the Formula One project and the rest of the BMW company do you consider to be the most significant?

MT:

For BMW, the flow of expertise between motorsport and production models was always a foregone conclusion. It was consequently part of the Executive Board's brief for our Formula One project and led to the team being closely linked to BMW's Research & Technology Centre in Munich. A key factor in the rapid set-up was being able to draw on the company's in-house expertise.

It means the engine management for the Formula One unit is entirely BMW-built - hardware, software, development and production - the work is done by the team that previously developed the electronics for the M3 and M5. But today there's just as much Formula One know-how being ploughed back into series production. Obviously you can't just take a component from an Formula One engine and put it into a production model without modification. The requirements and the design are far too disparate for that. What we're transferring is not technical hardware but technology. We have set up our own Formula One foundry and an Formula One parts manufacturing plant. Both factories are run by the teams also responsible for casting and processing production parts. The upshot is that these departments have at their disposal a technology laboratory where they can, at an accelerated pace, familiarise themselves with pioneering casting and production techniques, while at the same time meeting the extreme demands of Formula One regarding speed, flexibility and precision. One can already foresee how strongly this know-how is going to impact on BMW's next generation of production engines.

Q:

How many engine faults will you permit the P82 in the 17 Grand's Prix of the 2002 season?

MT:

If we were driving solely with the aim of finishing and picking up points, we could largely eliminate faults by using a conservative engine. But we want to be in there among the front-runners, and so with the P82 we will be pushing the envelope even further than with the P80 in 2001. That can only be done on the basis of our experience over the first two seasons, but it also requires the courage to take risks. One thing is clear, though: in 2001 we had too many technical faults, both in the engine and in the car. That's why our brief for 2002 has 'improved reliability' spelt out in bold letters.

Q:

Which phase of engine development is the most exciting for you?

MT:

There are several milestones which are just as exciting as any race. There's defining the engine design as an overall concept, finalizing the design, where every single day is crucial, building the first engine, the first test bench trial and then the first test run in a car. If everything works, the engine and the team then get their 'passed' certificate in Melbourne.

Q:

How do you like to spend your leisure time?

MT:

With my family and playing sports, preferably in the open air. Engine noise, for all that it means to me otherwise, I can do without.